Being the 57th edition of Assorted Nonsense, the official newsletter of Donovan Street Press Inc.

I’m doing my best to finish my latest novel, so haven’t had any spare time to craft any new, finely honed posts here on Substack. Fella’s gotta prioritize! And there’s only so much time in the day.

So I hope you don’t mind, but I’ve got plenty of spare writing sitting around to help tide us over.

Including this never-before-published short story, Man’s Best Friend.

Hope you like it.

Man’s Best Friend

Man’s Best Friend

By Joe Mahoney

“Thanks for the dog biscuits,” he said. “I really did enjoy those.”

He didn’t really say it, of course. He just thought it. And the device on his paw—not around his neck, never around his neck, not anymore—picked up his brainwaves and transmitted it through the tiny but effective speaker so that people like me could hear it. Hear what my dog had to say. Wait—not my dog. Not anymore. The dog who used to be mine. But who didn’t belong to anyone anymore.

I nodded. “I’m glad.”

We stood staring at one another awkwardly, me in the doorway in my pajamas, while my dog Buster—my former dog, I reminded myself—stood on the front porch, looking especially sharp in his new tartan suit, with two battered old suitcases in his paws—his surgically enhanced paws with the fancy new opposable thumbs. And then Buster turned and trotted out of my life. Leaving behind only memories. Memories of being the cutest puppy in the litter.

The puppies had all looked the same to me. It was Samantha who had picked Buster out, and Samantha who had named him Buster. “He just looks like a Buster,” she’d explained, so Buster he became.

Buster was a smart dog. Not smart like he would be, after the Alphans got through with him, but smart enough to make house training a lot easier. Samantha got him trained up on the bell, which he’d ring with his snout and either Samantha or I would let him outside to do his business. And he’d come right back inside. Somehow, he knew never to leave the property, or go on the road. Yeah, a smart dog. He learned to sit, and stay, and heel, and roll over, beg, play dead, and so on. By the time Samantha was through with him he was ninety percent trained. At least that’s what I told people. Buster didn’t always do what he was told, but mostly he did, because he was a smart dog. A good dog. A special dog.

I’d been sceptical at first. I hadn’t wanted a dog. Thought a dog would be a whole lot of bother. “You can have furniture or you can have animals,” I had warned Samantha. “But you can’t have both.” I hadn’t been wrong. Buster went through a “bitey” stage. Hands, slippers, and table legs got the worst of it. But I didn’t care. By then it was too late. I’d already fallen head over heels for the pooch. By then Buster was already “Poochie Woochie” and “Doggie Woggie” and other names no grown man should ever be heard uttering aloud to anything other than their new best friend.

Everyone loved Buster. This was no great surprise: Golden Retrievers are always popular. Gentle giants with great dispositions. Neighborhood kids flocked to pet him. Even Mrs. Robinson next door liked him, and she didn’t like dogs. She was afraid of them. But not Buster, because there was nothing to fear there. He didn’t bark, never caused trouble, and Samantha and I were always good about picking up after him.

We walked Buster at least twice every day, sometimes thrice. Samantha insisted that we keep him on a strict diet, so he got exactly what he needed to eat and nothing more, except the occasional treat. So, he was a good weight, and handsome, and gentle, and popular. The perfect dog. And before long he was an inextricable part of our lives, as though he’d always been with us, and always would be. Sometimes I thought about what it would be like when Buster was gone, but I never thought about it for long, because I knew that the end, whenever and however it came, would be painful. But I never imagined it would end with rocket ships and aliens and dogs carrying suitcases in their paws.

It so happened that I glimpsed one of the first ships to arrive. Just a silver streak overhead as I walked Buster in the park.

“What the heck was that?” my neighbour Balraj asked.

“No idea,” I said.

I’d been chatting with Balraj, whose white, short-haired mongrel Corderoy (part Beagle, probably) was chasing and wrestling with Buster. We’d both let our dogs off leash so they could play while we talked, never mind that it was a five hundred dollar fine if we were caught. We’d never been caught.

It was already out of sight, whatever it was. There was a military airbase about an hour east in Trenton. “An experimental aircraft, maybe.”

I didn’t think about it much more until I heard the news on the radio that afternoon. Something about mysterious ships landing all over the world. Speculation that they were Russian or Chinese ships launching an invasion was quickly cut short when it turned out that the ships were landing in those countries too, and that the creatures that disembarked looked remarkably like dogs, except that they walked upright and were quite obviously intelligent.

Events progressed quickly from there. Subsequent newscasts revealed that the aliens, for they were clearly extraterrestrial, were at least as intelligent as humans, and certainly much more technologically advanced. Because of their resemblance to canines, the media joked that they must be from the Dog Star Sirius, though that made no sense at all, as the Dog Star was not called that because of any connection to dogs. It turned out that the aliens were from Alpha Centauri, so they came to be called Alphans. Which turned out to be especially appropriate, as they quickly became the Alpha species on Earth.

Samantha and I (and Balraj and everyone else) watched the nail-biting events of the next thirty-six hours with great trepidation. Predictably, after a botched diplomatic effort, humans set aside our terrestrial differences and attempted to get the upper hand by unleashing our combined military might against the invaders, as our governments briefly tried to characterize them. But the Alphans, disciplined and prepared, surgically and almost casually castrated human military might with ease. Weapons did not fire against them. Nuclear bombs did not explode. It all ended when the Alphans finally pirated human airwaves and addressed all of humanity. Their spokesperson (spokesdog?) looked remarkably like an Alsatian. It sounded almost bored when it addressed humanity en masse, beginning with: “Are you quite through yet?”

This ushered in an era of unprecedented peace for humanity. Weapons were turned into ploughshares, as it were, and the Alphans began to re-organize Earth governments. They never actually took over. They had no interest in taking over. Their job, it turned out, was to introduce the Earth to the Galactic government. They were the military police, the vanguard. Humanity was gently but firmly forced into an era of enlightened civilization.

Not all life in the universe was related, they explained. Some had evolved in isolation. But sometimes life on distant planets was the result of migration. Such was the case with Earth. Several species on Earth were related to species on other worlds. Humans for one. Dogs for another. The Alphans were descended from the dogs on Earth. Or maybe it was the other way around; I can’t remember. I only know that the Alphans took an unfortunate interest in the dogs of Earth in a way that really messed things up for Buster, Samantha, and me.

It began with a registered letter ordering us to take Buster to something called an Acceleration Centre for evaluation.

“We could just ignore it,” I suggested to Samantha.

“They just conquered us,” Samantha said. “Do we really want to risk pissing them off? They could be watching us right now. Besides, the letter says they have Buster’s best interests at heart.”

“Do they.” I was not convinced but decided not to defy the all-powerful aliens.

At the Acceleration Centre we saw our first alien in the flesh. An actual Alphan, standing tall on its hind legs, regarding us with a pair of serene brown eyes, the whiskers on its brown muzzle twitching slightly as Buster ran up and began sniffing its legs, looking to make a new friend. The Alphan’s mouth did not move, but it spoke nonetheless.

“It’s good to meet you, Dan and Samantha Gallagher.”

We were both speechless in the alien’s presence. The Alphan was forced to repeat itself.

“Yes, yes, hello,” I said finally.

“My name is Rorapin.” The Alphan sounded female.

“It’s nice to meet you Rorapin.” I meant it. I had a good feeling about the alien. Maybe because she looked like a dog. And I just happened to really like dogs. And of course, it was cool meeting an alien, from a race of aliens who deliberately hadn’t killed any humans, even though humans had tried to kill them

Rorapin gave Buster a thorough inspection. “Buster looks well cared for,” she observed, making a note on an electronic pad. Opposable thumbs, I saw.

“We do our best,” Samantha said.

Rorapin led us to a reception area where we could all sit comfortably. Rorapin did so as well, and crossed her legs, a remarkable sight.

“Dan and Samantha Gallagher, you want what’s best for Buster.” It was not a question.

“Of course,” Samantha said.

“Good. That will make this much easier.”

“Make what much easier?”

“Buster will be among the first to be accelerated. We believe the process will work especially well on this breed. Golden Retrievers.”

“What do you mean by accelerated?”

“Many animals on this planet have untapped intellectual capacity. Dolphins, octopi, elephants, great apes, chimpanzees, and dogs, to name a few. A part of what we do when we contact planets like yours is provide opportunities for members of those species to realize their potential. We believe Buster has this potential.”

“He is smart,” Samantha acknowledged.

“Nowhere near as smart as he will be,” Rorapin said. “We’re capable of providing additional modifications too, which will help him further realize his potential. Wouldn’t you like to see that?”

Samantha and I exchanged glances, none too sure.

Rorapin assured us that Buster wouldn’t be hurt. That we would get to keep him after the procedure. That this would ultimately help many other dogs. The clincher, for both of us, was when Rorapin told us about the potential impact on Buster’s life span. That Buster’s lifespan would ultimately increase by as much as fifty, sixty years.

“There are no guarantees,” she said. “There’s always the chance of accident or some unforeseen medical issue. But typically, we see a great increase in longevity.”

We couldn’t deny Buster that. After that it was a no-brainer.

There was only one more question:

“What about cats?” Samantha asked. “Do you do this for cats too?”

Oh, how Rorapin laughed.

On the appointed day we brought Buster to the Acceleration Centre. Other owners were there too, looking as nervous as we felt. “Take good care of him,” I instructed Rorapin as she took Buster away.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “Buster is as important to us as he is to you.”

I doubted that.

After the procedure we weren’t allowed to see Buster for several weeks. Rorapin did provide updates, though. Buster’s doing fine, she told us over the phone. He’s making remarkable progress, she wrote in an email. He’ll be coming home soon, she told us in person, during a visit to the centre to prepare us for just that.

“Think of Buster as a child,” Rorapin told us that day. “A child who has grown up.”

“We have children,” Samantha told her. “Who have grown up. It’s true that they were kind of like Buster once. They couldn’t talk or take care of themselves. We had to do everything for them, until they became independent. But that process took years. We hardly noticed the changes as they happened. It’s not going to be the same with Buster.”

“No,” Rorapin admitted. “Buster has grown up in a matter of weeks, and you didn’t get to see any of it. But you will get to see him tomorrow. And you will see that he’s still your Buster.”

But he wasn’t. Neither Buster nor ours. I’m sure Rorapin didn’t mean to lie, because Alphans don’t lie. They are resolutely honest. Like all Alphans, she meant well. But just because you mean well doesn’t mean you do well.

“Hello,” he greeted us that first day.

He was sitting in a chair in the recovery room. He couldn’t walk yet because of the extensive surgery to his back and knees and probably a bunch of other parts, but he was healing quickly, thanks to Alphan medicine. There was a faint odour of wet dog in the air. He must have just had a bath. He’d always been good about baths.

Samantha was the first to recover from the shock of hearing him talk. “Hello, Buster. How are you?”

“My name isn’t Buster anymore,” he said.

I found I had to sit down. “What?”

“I’m sorry. I know that’s your name for me. Buster. But I’ve decided to change my name.”

It had taken me a moment to locate the source of his voice: a circular device strapped to his paw, like a watch. The voice the device produced was warm and resonant, just the sort of voice you would imagine a dog would have if it was large, friendly, and could talk.

Samantha took a seat as well. “Why?”

“Because I’m not that dog anymore.”

“Okay,” Samantha said. “I can understand that. What’s your name now?”

“Reginald. I would prefer to be called Reginald.”

I guffawed. “You’ve got to be kidding.”

Perhaps I offended him.

It was pretty much downhill from there.

He came home a week later, on his own two paws. The Acceleration Centre had provided a list of meal suggestions now that we could no longer just feed him dog food. Reginald was going to cost us a fortune in steaks and burgers. Less work, though; Reginald had learned to cook at the centre. I would find him hunched over the stove searing up a T-Bone or Rib Eye at all times of the day and night. And he could walk himself now, which was great, although I often accompanied him at first, just to make sure he knew the way, and to try to get to know him better.

“Do you remember much?” I asked him on our first walk together, as we rounded the bend into the park, underneath the pines. “From before?”

“Yes,” he said. “I do.”

He didn’t say much more then. I thought it was because of other people on the path, staring at us, making him feel self-conscious, but that wasn’t it. It was because he had more to say, and didn’t want to say it, because he was, in a way, the same old Buster. He had a good heart, just bad memories.

It all came out later, bit by painful bit.

I honestly thought we had been good masters. We had fed him, housed him, walked him, took him to the vet regularly. Petted him. Bathed him. Groomed him. Even brushed his teeth. Never laid a hand on him.

“It’s true,” he told me. “You did all that. I remember. It’s like a dream, but I remember.”

But that wasn’t all he remembered.

One day, on another walk, he confessed, “I was hungry all the time. I know you think you were doing the right thing, keeping me on a strict diet, but all I could think about was food. All the time! You would give me a bowl of dog food which I would gulp down in seconds, and a few treats here and there, and that was it. Meanwhile all of you would think nothing of eating in front of me. You would eat whenever you wanted, as much as you wanted, and I would lie there hoping, praying that you would drop something, and if you did I had to pounce on it right away before one of you told me to leave it.”

I was stunned. He’d been a beautiful dog, exactly the right weight, slim waist, and that was because we’d looked after him. We were quite proud of that. It never occurred to me that it might be a source of suffering for him. Not long after that conversation he began to grow a bit paunchy. All those steaks. And he developed an unfortunate taste for ice cream.

That wasn’t all.

One day I took him out for a Sunday afternoon drive. We drove in silence for a while, as he stuck his head out the window, and I thought for a while that it was just like old times, until he withdrew his head, rolled up the window, put his seatbelt back on, and said, “Remember the leash?”

My whole being clenched. I just about drove off the road.

“What about it?” I asked as nonchalantly as I could.

“God, I hated that thing,” he said, almost to himself. “If I could have chewed it into little bits I would have.”

“I don’t blame you,” I told him. “But we had to have you on leash. City bylaws. And I couldn’t just have you chasing off after squirrels. What if you got hit by a car?”

“I know.” He scratched the side of his head for several seconds. Fur everywhere; I’d have to vacuum the van afterward. “But you used to yank me with the leash. All I wanted to do was sniff a bit, or pee. Why did you always have to be in such a rush? It hurt my neck.”

I flushed with shame. I couldn’t think of anything to say. “Sorry,” I said finally.

He didn’t accept the apology. No reason he should have, really.

One day, over supper (more steaks!) he started in on how bored he used to be, lying around the house all day, alone with nothing to do while we were at work. It had gotten worse after the kids left for university. “And even when you were home you’d just ignore me while you watched TV or read books or whatever. It’s not like I could do any of that. Couldn’t you have walked me more, or played with me? I loved playing fetch. Just a little fetch every now and then. Would that have been so much to ask?”

Naturally I’d shared with Samantha everything he’d told me so far. By now she’d heard enough. In tears, she said, “Look. We did the best we could. If you can’t appreciate that, too bad! It’s not like we knew that one day you’d turn into a freakish talking dog and do nothing but complain all the time!”

He laid down his knife and fork, with half a steak left—not a good sign for a full grown, healthy dog. “Is that what you think? That I’m a freak?”

Samantha’s eyes blazed. “Well aren’t you? Look at you. You used to be such a loving dog. All the kids in the neighbourhood adored you! We all did. Now everyone’s afraid of you. The kids won’t even come close. You’re not a dog anymore. You’re not human. You’re not even one of them!” She meant an Alphan. “I’m not sure what you are. And I’m not even sure I care anymore.” She slammed her own utensils down, violently pushed her chair back, and stormed out of the dining room.

Reginald and I sat there awkwardly until he too got up, mumbling something that I couldn’t quite make out, but that could have been, “I really hate this.”

And that was pretty much it. I guess he got a hold of the Acceleration Centre on his own and made arrangements to leave. By then the Alphans had developed occupational training programs that he could take, to prepare him for the real world. The real world! What a joke. We had left that world long ago, the day the Alphans came.

And that morning he stood there with his suitcases in his mutated hands and said, “Thanks for the dog biscuits. I really did enjoy those.”

I stared into the deep brown eyes of the dog that once upon a time had been mine, who had been my best friend, understanding now that I had never been his.

“You’re welcome,” I told him.

We stood there awkwardly for a few seconds, and then he made his way down the steps toward the taxi waiting in the driveway, not once turning around, and the taxi drove off, and I never did see that damned dog again.

The End

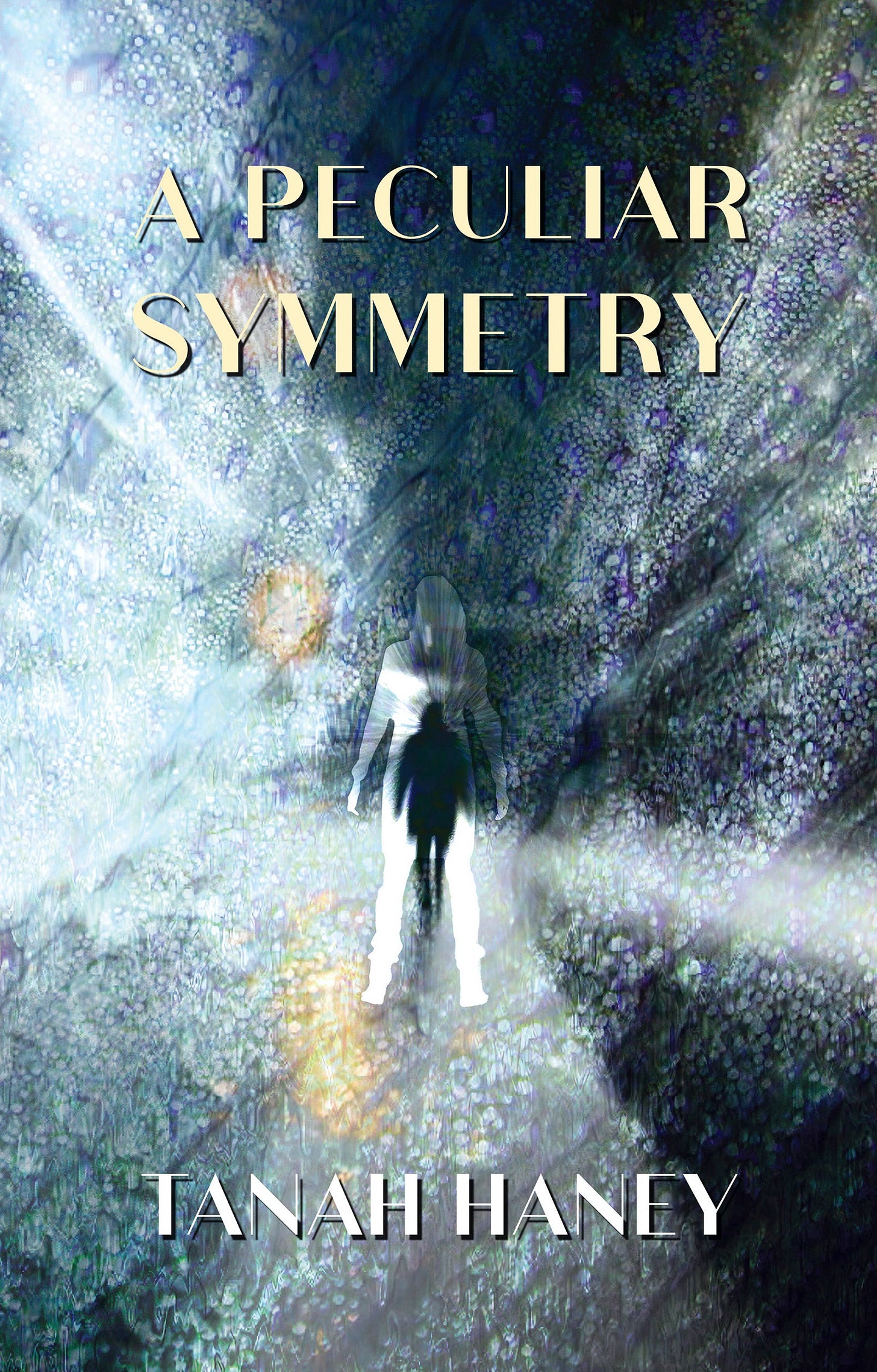

A Peculiar Symmetry

by Tanah Haney

Aiden and Minnie. Two of the least ordinary people you’re likely to meet.

Aiden’s missing the first eight years of her life, yet she can play Beethoven’s Concerto without ever having been taught. Minnie can see people’s emotions, in vivid colour, no less. That doesn’t help much when she meets Aiden, who doesn’t seem to have any.

When British Intelligence sweeps in, along with belligerent spies and a half-brother Aiden never knew existed, Minnie soon discovers that whatever Aiden might lack, she more than makes up for in intrigue. Getting to know one another will have to wait, though; when bullets start to fly, and the bodies begin to pile up, the two young women find themselves caught up in a clandestine war for control over the human psyche…and their own lives.

The book is exceptionally well-crafted. ~ Dave Morris, Amazon Review

About the Author:

When not writing, Tanah Haney divides her time between playing the Celtic harp, teaching music, gardening and cat wrangling. She is a published poet and is co-author of Where the World Bleeds Through with her husband, photographer and digital artist Mark A. Harrison.

The character of Aiden in Tanah’s debut novel, A Peculiar Symmetry, was inspired by Tanah’s own experience with neurodiversity. Late diagnosed with ADHD at age 50 but neurodivergent from day one, Tanah is determined to be a more vocal champion of everyone who has ever felt different, and for the free expression of same in a diverse, inclusive, and compassionate society.

Tanah lives in Peterborough, Ontario, with her husband Mark and a small but vocal menagerie.

Podcast

Re-Creative: a podcast about creativity and the works that inspire it.

Mark A. Rayner and I recently took part in Podcasthon, "The world’s largest podcast charity initiative, bringing together podcasters globally to raise awareness for charitable causes."

We dedicated an episode of Re-Creative to support Meals on Wheels Summerside, a charity my mother, Rosaleen Mahoney, and my sister, Susan Rodgers, have supported for years.

The episode we're dedicating to Meals on Wheels features Ruth Abernethy, a sculptor of some of the most iconic public art in Canada. If you've heard this episode before, it's worth another listen. If you haven't heard it, we think you'll enjoy checking it out.

Please join us in supporting Podcasthon and Meals on Wheels!

All previous episodes are available online, comprising the first 3 seasons, over 60 conversations with creative people from all walks of life about the art stoking their imaginative fires.

Thanks for reading!

Follow Joe Mahoney and Donovan Street Press Inc. on: Goodreads, Bluesky, Threads, Mastadon, Facebook, and Instagram

This has been the 57th edition of Assorted Nonsense, the official newsletter of Donovan Street Press Inc.

"they must be from the Dog Star Sirius, though that made no sense at all, as the Dog Star was not called that because of any connection to dogs..."

The alien canine race my fictional superheroine Cerberus is part of originated around that part of the universe, so knowing the truth about it is surprising to me.

It probably would be a surprise as well to novelist Olaf Stapledon, who wrote about a similarly "uplifted" dog named Sirius, and probably to the Alan Parsons Project as well, since one of their best known tracks is an instrumental by that name.