Being the 39th edition of Assorted Nonsense, the official newsletter of Donovan Street Press Inc.

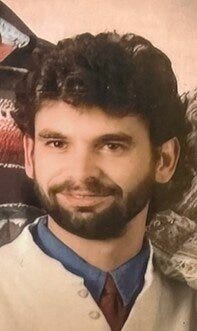

The story of Jane begins and ends with her brother Paul

Paul was my best friend one summer. Just that one summer, really. But that summer he was the kind of friend that Stephen King was thinking of when he wrote in his story The Body:

“I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was 12 - Jesus, did you?”

I was a bit older than 12 but it doesn’t matter; Paul was that kind of friend. He was one year younger than me but he felt the same age, if not older. He had older brothers and sisters. I didn’t. His elder siblings had conferred upon him knowledge and wisdom that nobody had given me. He possessed a sophistication that I lacked.

Paul lived around the corner from my house. Part of the backyard of his house jutted up against our backyard. I can’t remember how or why we started hanging around; we just did. We lived so close that probably we just bumped into each other one day and hit it off, though we would long have been aware of one another. This would have been before summer jobs came along to monopolize our summers. It was a time of freedom. Of waking up in the morning, wolfing down breakfast, and then hopping on your bike and spinning around the neighbourhood to see who was around. Summers meant baseball, marbles, biking, street hockey, ice cream, going to see a movie, or just plain hanging around doing nothing. Life was good, unless your father managed to rope you into some silly chore, like weeding or mowing the lawn; it was important to get out of the house early.

Paul and I spent a lot of time on our bikes. We never wore helmets. I had at least two bike accidents that I can remember. Once I braked too hard and flew over the handlebars. Scraped my bare knees on the asphalt pretty good but didn’t hit my head. Another time I rounded a corner going way too fast, didn’t make the turn and smashed full speed into a brick wall. A cedar bush reduced the impact a fraction but scratched me up pretty good. Again I managed not to hit my head. I arrived where I was going (basketball camp) bloody but unbowed.

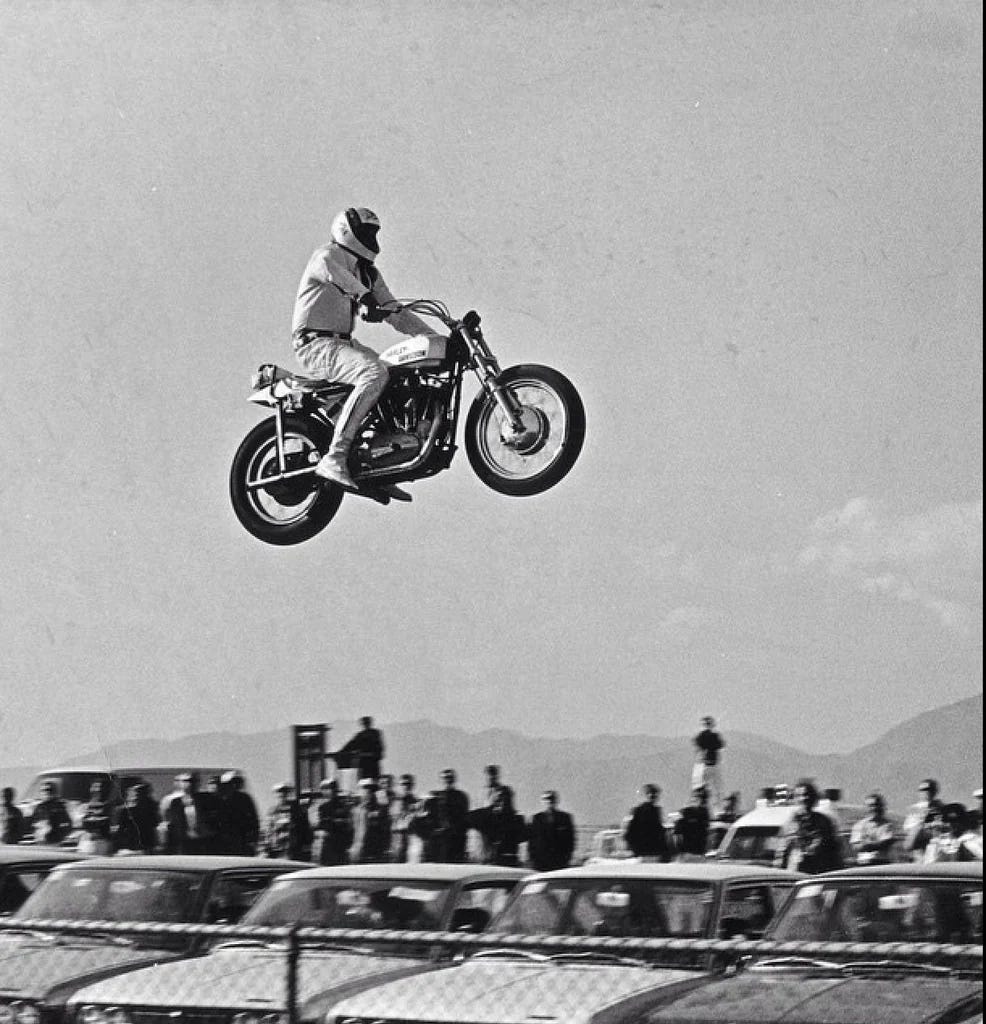

Paul’s great ambition was to be a stuntman. I don’t remember him ever crashing his bike. I can’t remember if he wanted to be a stuntman for movies or one like Evel Knievel, who jumped canyons and was big those days, but I could totally see Paul as either. He had the right spirit. And it just seemed within the realm of possibility. I wanted to be an actor. At the time, I absolutely believed that Paul would grow up to be a stuntman and I would grow up to be an actor. The future was a magical place where anything could and probably would happen, and it would be golden and good.

Paul and I became good friends because we didn’t just hang around, we spent a lot of time talking. About our dreams. About life. Making sense of it all.

“Do you think you’ll ever move away from here?” he asked me one lazy summer day.

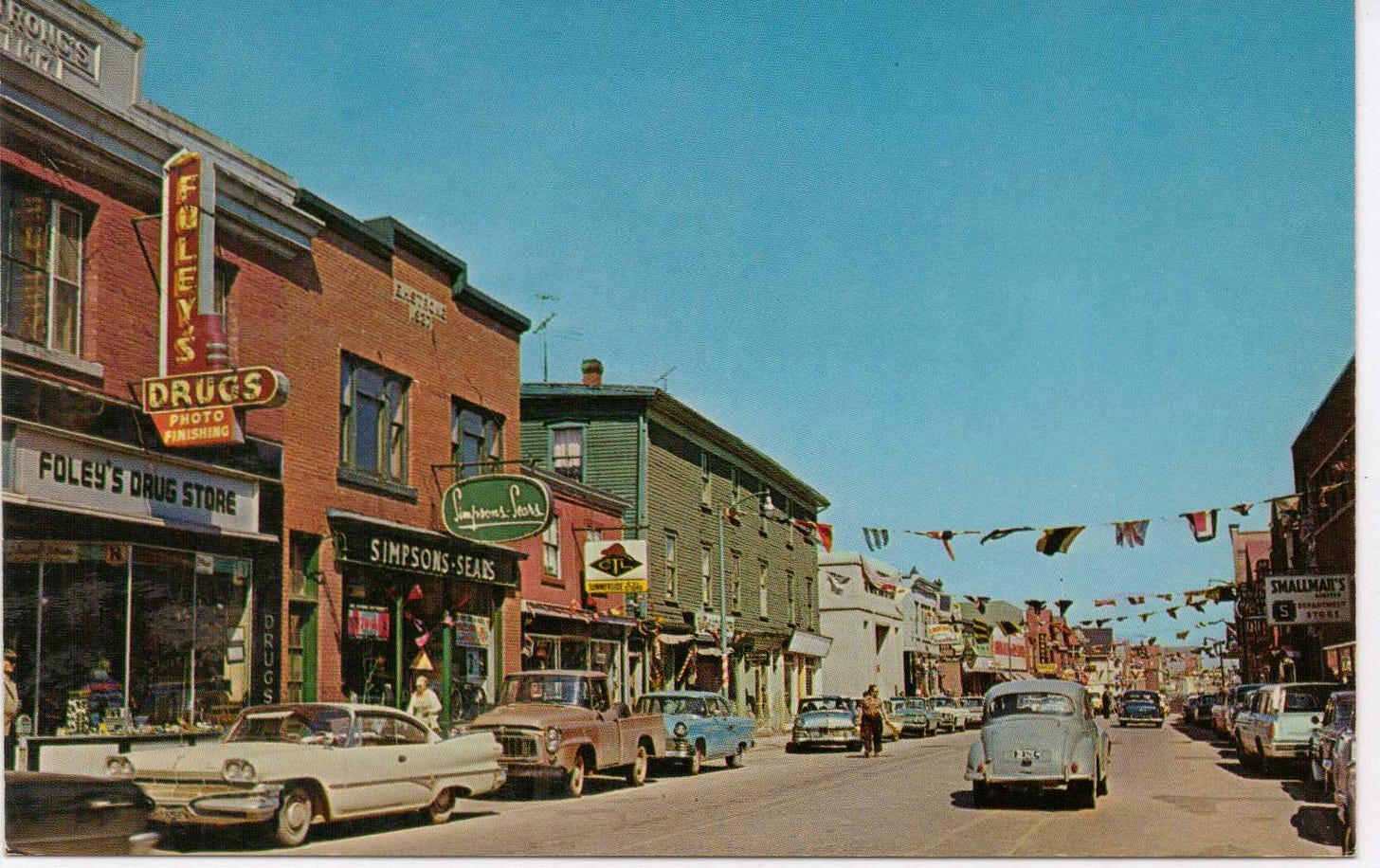

“No,” I told him truthfully. “I like the island.” I couldn’t imagine ever having to leave PEI.

Though Paul and I hung around a lot that summer it’s difficult to pin down precise memories. I remember long bike rides. Practising simple stunts. Riding up and down the concrete ramp at the Presbytarian church down the street (beneath which it always smelled like urine). Making recordings on my father’s cassette recorder, pretending we were disc jockeys (I still have those recordings around here somewhere). Music blasting. Van Halen was everywhere that summer. The Knack’s My Sharona. Prism’s Armageddon. Blondie’s Heart of Glass.

We spent one memorable day at Twin Shores beach. We joined a big volleyball game. I played well; that one volleyball game may be the best I’ve ever been at sports. On a hayride around the Twin Shores property I conducted an experiment with memory. The haywagon rode over a rock on the dirt road. I made it a point to remember the physical features of that rock. Over the next few days I would visualize that rock on the road, locking it into long term memory. I wanted to see how long I could hang onto a single memory. Today, at least forty-four years later, I still remember that day, the vollyball game, the hayride, and the rock. But as I scour my brain for specific memories of Paul, with whom I know I spent much of the summer, the memories are disappointingly sparse.

We can choose our memories by writing them down. By taking photographs, talking about them, or consciously locking them into long-term memory. But the rest of the time memories choose us. One day many years later I was touring the textile gallery of the Royal Ontario Museum with my sister Susan. Spotting a multicoloured blanket on display, Susan turned to me and asked, “Remind you of anything?”

I laughed and told her. The blanket was the spitting image of a Hudson’s Bay wool coat Paul’s mother used to wear. The black, red, yellow and green stripes on white were so iconic that the image had been burned into our brains, inextricably associated with her.

Paul had an older sister, Jane. Jane was one year older than me. I have several pleasant memories of Jane. Here’s one. At school one day some kid took my toque and threw it in the girls’ washroom as a joke. Obviously I couldn’t go in after it.

Jane happened along.

“Somebody threw my hat in the girl’s washroom,” I told her. “Could you get it for me?”

Jane retrieved my hat for me without any fuss or bother. I thanked her and she your welcomed me and continued on her way.

A pretty inocuous event, I know, but it’s the little kindnesses you remember. Especially after you are given reason to reflect on somebody’s life.

The summer ended and Paul and I didn’t see much of one another in the months that followed because we were in different grades. One morning I woke up to the sound of my mother vacuuming outside my bedroom in the basement. I have always remembered it as being around October but looking it up just now I see that it was actually April. Again, the vagaries of memory.

My mother opened the bedroom door. She was in tears and vacuuming unusually aggressively, taking her frustration out on the carpet.

“Too young,” she said cryptically. “It isn’t fair!”

Gradually the story came out.

Apparently, Jane had finished a late shift at McDonalds and some fellow staff offered her a ride home. She didn’t wear a seatbelt because seatbelts didn’t become mandatory in Prince Edward Island until several years later. They took the long way home. Somewhere along the way the car left the road. I don’t know why. It was an accident, bad luck, pure and simple. Jane died on the scene in the arms of a policeman, I was told.

She was only fifteen.

I cannot tell you how many times I have thought about Jane since then. She is on a short list of people that, if I could travel back in time, I would go out of my way to save. I would do whatever it took to save her, if only I could.

Paul was obviously deep in grief the next time I saw him. It was apparent in what he said and in the way that he said it and in the chasm that had opened up between us. Just a kid myself, I didn’t know how to console him, how to help him any more than I knew how to go back in time to save his sister.

I hardly saw Paul after that. Sometimes I think that it is one of the great failures of my life: that I couldn’t be there for him. I just didn’t know how. But the truth is I probably wouldn’t have made much of a difference.

And then in the blink of an eye we became adults. Paul never became a stuntman, and I never became an actor.

I had long since moved away from the island and was back to visit my family when Paul and I happened to run into one another on the sidewalk in downtown Summerside.

“Look at all the grey!” he teased me, eyeing my prematurely greying scalp.

We chatted briefly, superficially, the way you do when you’re not Stephen King-type friends anymore.

“I’m so glad to have run into you,” I told him as we parted, imbuing the words with as much sincerity as I could muster because I did truly mean it.

I had not forgotten just how good friends we had been once, briefly, before tragedy, time and life propelled us along separate paths, and I hoped Paul hadn’t either.

On September 21st, 2024, Paul Joseph Wedge joined his sister Jane Elizabeth, his brother John (J.J.), and his father Jack in whatever comes after this perplexing life.

Follow Joe Mahoney and Donovan Street Press Inc. on: Goodreads, Bluesky, Threads, Mastadon, Facebook, and Instagram

This has been the thirty-ninth edition of Assorted Nonsense, the official newsletter of Donovan Street Press Inc.